|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series NEPAL |

|

|

|

475-512 |

|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series NEPAL |

|

|

|

475-512 |

|

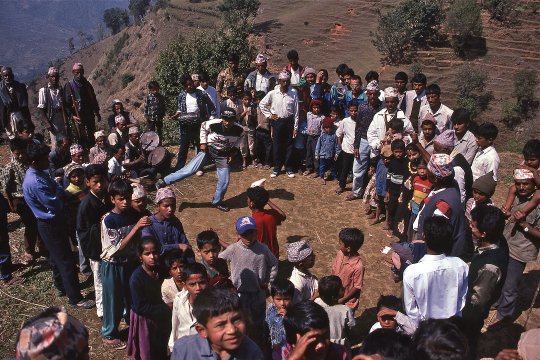

| 481. While they waited for the feast which would be provided by the bride’s family, the guests were entertained by dancers, again only male, though I’m told that women may dance at the bride’s house. |

|

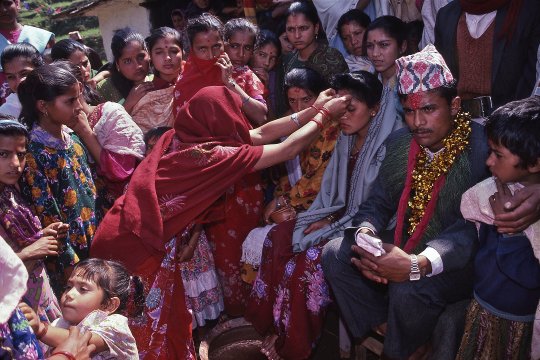

| 487. She will then mark their heads with tikas of rice, and give either or both of them a small bundle of banknotes. |

|

| 495. The bride is now taken inside the house to change into the clothes she has been given, while the groom joins his friends in the fields below to enjoy the wedding feast. |

|

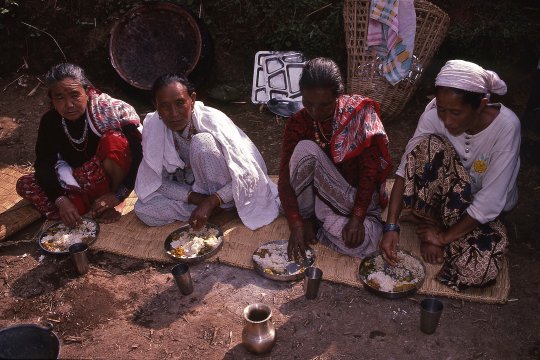

| 498. The meal was a standard dhal bhat tarkari with minor embellishments, and it was distributed in bulk to the rows of diners seated cross-legged. |

|

| 499. The older women who had been invited ate separately, but many of the younger ones went without at that time. |

|

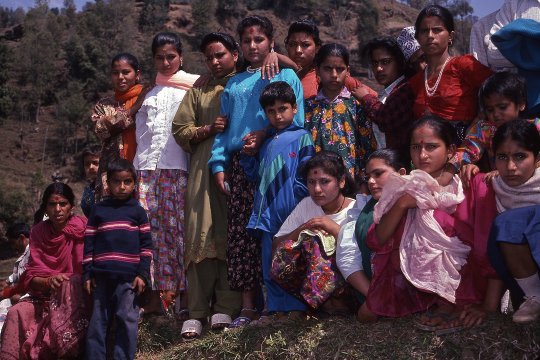

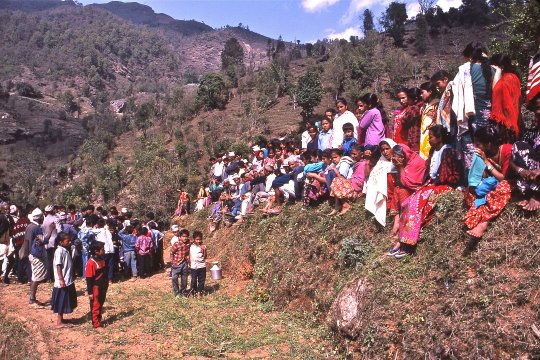

| 500. They lined up outside, watching the action on the terraces below. |

|

| 501. The musicians continued to play and dancers who were tired were simply replaced. |

|

| 507. Attention once again shifted to the fields below, where dancing continued, watched by crowds arranged over what resembled the “banked seating” of a theatre. |

|

| 508. The groom joined them, while everything was being packed up in readiness for the walk to his village led by the same musicians, for there would be further celebrations when they got there. |

|

| 509. His bride was left on her own to meet with her friends at the Welcome Gate where the groom and his friends had been received earlier in the day. They did their best to comfort her. |

![]()

Text, photos and recordings

by John Tyman

Intended for Educational Use

Only.

Contact Dr. John Tyman at johntyman2@gmail.com

for more information regarding

licensing.

![]()

www.hillmanweb.com

Photo processing, Web page layout,

formatting and hosting by

William

Hillman ~ Brandon, Manitoba ~ Canada