|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series NEPAL |

|

|

|

190-228 |

|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series NEPAL |

|

|

|

190-228 |

|

| 191. Nepal is a land of man-made trails, not roads. (Near Pisang) |

|

| 192. These are broad in places but are in no way suited to vehicle traffic, so everything has to be carried -- on two legs or four. (Near Jomoson) |

|

| 193. Horses are the preferred means of personal transport for those able to afford such luxury. This one was ridden by a trader heading for Chame, the administrative centre of the Manang District. |

|

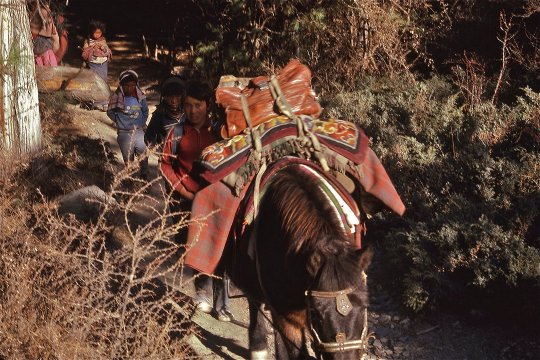

| 194. Ordinary folk tie their baggage to their horse and walk behind it. (Near Pisang) |

|

| 195. In the Mustang District some people still use yaks or yak hybrids. (Arriving in Jomoson) |

|

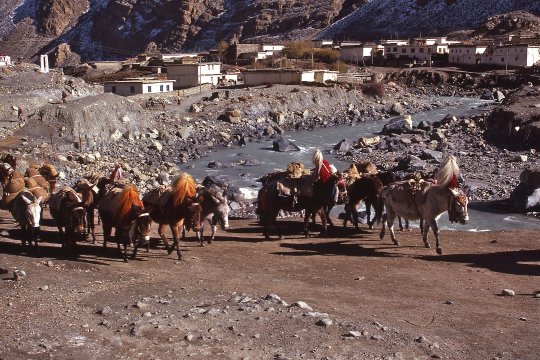

| 196. But traders here today use horses or mules: and animal caravans like this are a common sight following both the Marsyangdi and the Kaligandaki rivers. (Near Chame) |

|

| 197. Since many trails have been cut into cliff faces high above the river they offer the unwary traveller the prospect of certain death. (Approaching Pisang) |

|

| 198. Blind corners are a particular hazard, as it is all too easy to to swept off the cliff by a line of excitable draft animals! |

|

| 200. The other danger is landslides, after rains especially. Old trails will be buried and a way must be found around such obstructions. (Near Chame) |

|

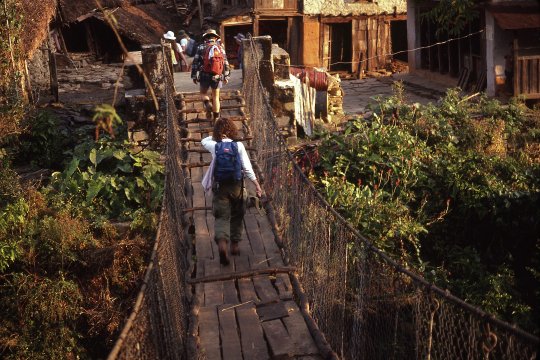

| 203. Others are supported by ropes and cable, sometimes high above the river: and the older ones do not inspire much confidence in visitors! (North of Tal) |

|

| 204. For that very reason, most have been rebuilt, using heavier cables and cross-bracing as protection against strong winds. (Near Tal) |

|

| 205. Most bridges are floored with planks of wood, but you may well find some are missing and others are rotten. (Near Phalenkangu on the lower Marsyangdi) |

|

| 207. Instead the remotest communities depend on porters to supply them, often over great distances with overnight stops along the way. (Near Pisang) |

|

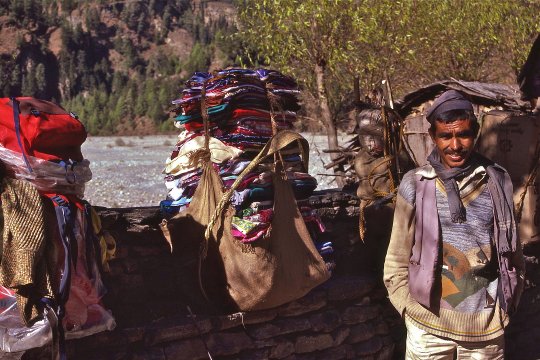

| 209. This man, near Larjung, carried supplies for tailors along the Kaligandaki. |

|

| 211. Everything and anything that could be formed into a manageable load was moved by two-legged transport. This man was delivering wheelbarrows south of Tatopani. |

|

| 213. These women carried gear for the camp kitchen of a party of tourists from Australia and New Zealand. (Near Phalenkangu) |

|

| 216. The bridges they must use cannot always be trusted, and many hang high above both rivers and rocks. (Near Tal) |

|

| 219. Most organized treks are led by local guides like these. They arrange for porters, plan the meals and campsites, and watch over the health of their customers. |

|

| 220. Their visitors carry only small day packs: the bulk of their gear is carried for them, together with their bedding, clothing, and tents. (Near Kalopani) |

|

| 221. Their meals are cooked along the way by people who have hurried on ahead so the food will be ready when they get there. (Near Tal) |

|

| 223. Other trekkers -- “the independents” -- travel alone. They do not normally carry tents but stay at the guesthouses located at strategic points along all the trails. This one was at Kalopani. |

|

| 224. The accommodation that these provide is simple but adequate, and it is usually well decorated. (Near Phalenkangu) |

|

| 225. Meals can be had in the same building or at one of the many tea houses. Tibetan butter tea is usually offered to trekkers but rarely accepted. (At Bagarchhap) |

|

| 226. Alcohol in one form or another will be available here too - for the benefit of trekkers and low caste Hindus. (Near Chame) |

|

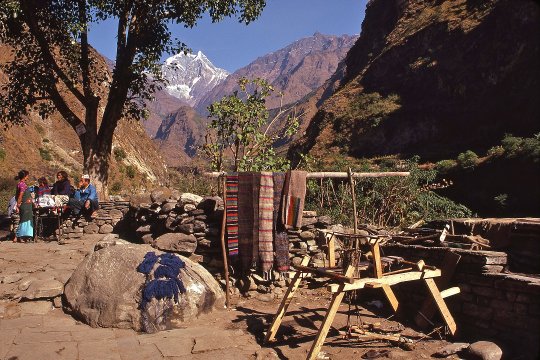

| 227. Outside they will be offered locally made handicrafts. (Tatopani) |

|

| 228. And a range of artifacts may be purchased, some ancient, others modern: but all souvenirs of a visit to the high country. (Ghorepani) |

![]()

Text, photos and recordings

by John Tyman

Intended for Educational Use

Only.

Contact Dr. John Tyman at johntyman2@gmail.com

for more information regarding

licensing.

![]()

www.hillmanweb.com

Photo processing, Web page layout,

formatting and hosting by

William

Hillman ~ Brandon, Manitoba ~ Canada