|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series Torembi and the Sepik A Study of Village Life in New Guinea |

|

Topic No. 20: Getting Married ~ Photos 386 - 422 |

|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series Torembi and the Sepik A Study of Village Life in New Guinea |

|

Topic No. 20: Getting Married ~ Photos 386 - 422 |

|

| 392. However, it’s impossible to raise a thousand dollars overnight. As a result it’s common for a couple to have one or two children by the time the official wedding ceremony takes place. |

|

| 405. As she left her father’s house the bride walked over her relatives, in another symbolic act separating herself from them. She would no longer belong to her father's family, but to her husband's. |

|

| 406. The procession then set off, leaving the bride’s former home in Torembi Three, and moving to that of the groom in Torembi One, three kilometres away. |

|

| 407. The bridal party wound its way through the bush, along forest paths and over log bridges crossing the gullies. |

|

| 410. The route then ran through sago swamp, but the procession crossed it easily on the logs provided. And from there it was only a short distance to the northern end of the groom’s village. |

|

| 412. Most of the women wore traditional, home-made garments, but those who’d been to secondary school in Wewak displayed appropriate items of mass produced underwear. |

|

| 414. The rhythm to their dancing and chanting was reinforced by a musical instrument they’d invented … a bilum full of beer bottles (visible on the right) that clinked loudly. |

|

| 418. In her case, the dancing continued long after she’d entered her new home, although it was hot inside and everyone was sweating profusely. She sat there, and the women danced around her, singing. |

|

| 419. Not all weddings are the same, though. At another one I attended the bride did not have to go far … just a few yards, to a neighbour’s house. |

|

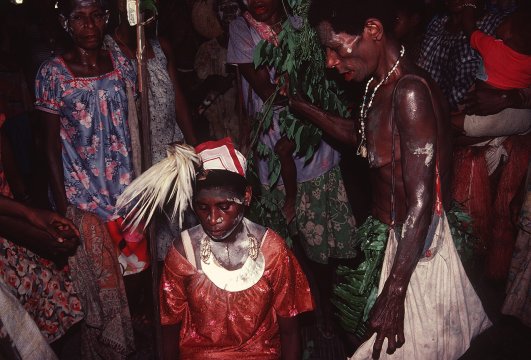

| 420. She wore the usual bird of paradise feathers and carried two spears, but hardly anyone else got dressed up, and the men did most of the singing. |

![]()

![]()

Back to

Cultures in Context Intro: Photos & Recordings

![]()

Text, photos and recordings

by John Tyman

Intended for Educational Use

Only.

Copyright Pitt Rivers Museum,

Oxford University, 2010.

Contact Dr.

John Tyman for more information regarding licensing.

![]()

Photo processing, Web page layout,

formatting, and complementary research by

William Hillman ~ Brandon, Manitoba

~ Canada

www.hillmanweb.com