|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series AFRICAN HABITATS : FOREST, GRASSLAND AND SLUM Studies of the Maasai, the Luhya, and Nairobi’s Urban Fringe |

|

|

|

|

|

John Tyman's Cultures in Context Series AFRICAN HABITATS : FOREST, GRASSLAND AND SLUM Studies of the Maasai, the Luhya, and Nairobi’s Urban Fringe |

|

|

|

|

Click for full-screen images

|

| 103. Posts are first dug into the ground 20 or 30 cm apart. Thinner horizontal pieces of lighter material are fixed across the uprights, both inside and out. The roof is framed in lighter material. |

|

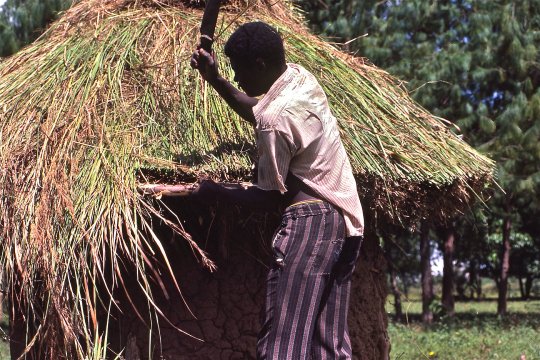

| 105. The roof is thatched with grass or reeds, depending on what is available. |

|

| 106. There are no chimneys. The smoke simply finds its own way out through the thatch. |

|

| 107. Lime is sometimes added to the plaster to stabilize it, and decorative patterns may be applied to the outside of the house. |

|

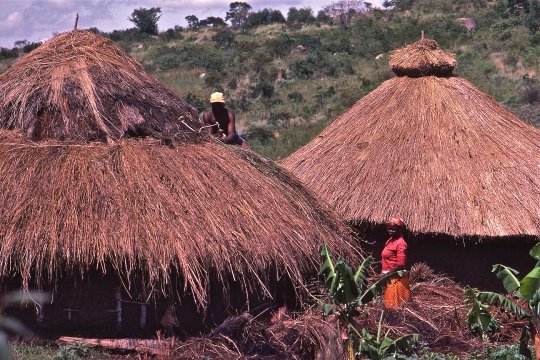

| 108. Thatching is in most cases a strictly utilitarian exercise, to shelter the occupants from the sun and the rain with no attempt at decoration. |

|

| 109. In some Luhya households, though, the thatch was stepped ... in this case over an experimental square frame. |

|

| 111. The thatch, too, would have been replaced periodically … typically every 4 or 5 years. |

|

| 113. Instead corrugated iron is often used today, and such houses are no longer round. |

|

| 114. A few householders even recycle tin cans, flattening them out and attaching them as shingles. |

|

| 115. The granaries (actually corn cribs) start out as large purpose-built baskets which can be purchased locally. |

|

| 116. The roof of the crib is assembled on the ground, tied to the top of the basket, and then thatched. |

|

| 118. This is the room where meals are eaten and visitors entertained. |

|

| 119. The fire-place in the kitchen behind will typically have three stones (or clay cones) ... since it is difficult to balance anything properly on four. |

|

| 120. It will be equipped also with a series of pots in which water and foodstuffs can be stored prior to use. |

|

| 121. Chickens will wander in and out, and may well lay their eggs here. |

|

| 122. The bedroom opposite will have a fire of its own for warmth; but it is difficult to fit rectangular bed frames into a space with curved walls. |

|

| 123. Today, outside the house but inside the fence there will likely be a toilet, a “bathroom”, and a rack for dish washing. |

![]()

Text, photos and recordings

by John Tyman

Intended for Educational Use

Only.

Contact Dr. John Tyman at johntyman2@gmail.com

for more information regarding

licensing.

![]()

www.hillmanweb.com

Photo processing, Web page layout,

formatting and hosting by

William

Hillman ~ Brandon, Manitoba ~ Canada